Getting Started with the Linux terminal

Getting Started with the Linux terminal

For many people just starting out with using Linux, the terminal can be quite intimidating, but, whilst it might be difficult in the beginning, can save you a lot of time if you know your way around in the terminal, as, if you have to lift your arm up from your keyboard to use your mouse one fewer time, it can lead to using a few seconds less - for every time you do this action. Over time, the effort you put in to learn the Linux terminal will pay out.

Which shell to choose?

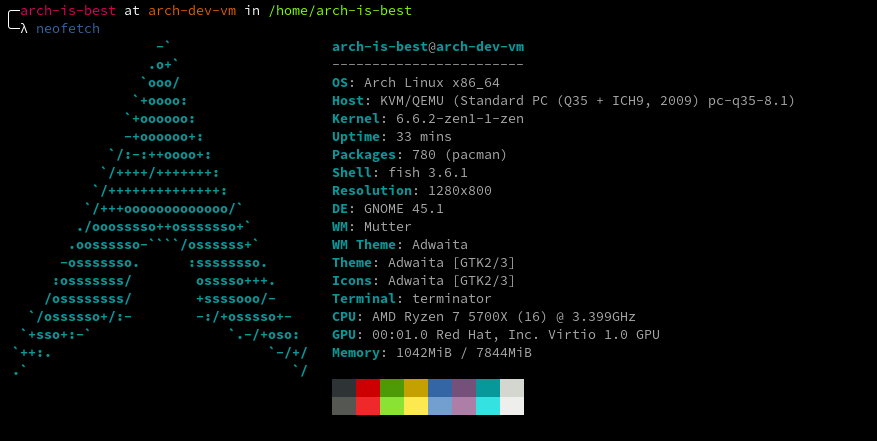

On Linux, as always, there isn’t just one shell. At the time of writing this article the most popular shells are fish, bash and zsh. They are all slightly different, but I won’t go over their differences here. Personally, I use the fish shell, as it has a few neat features, most notably that it shows a hint for what the command you might be writing might be, without having to press tab. In general, fish looks neater than bash and zsh. If you have installed the Arch Linux Development Virtual Machine, the fish shell has been configured for you automatically.

You can check what your current shell is by typing

echo $SHELLThis will spit out the path to the shell. The part behind the last / tells you which shell you are using.

You can change your shell by typing

chsh -s /bin/[shell name here]You will be prompted for your password.

The basics

We are going to look at some simple commands for the terminal which are exactly the same, regardless of what shell you are using.

The first important aspect is, always use autocompletion, as it can help you type faster and with fewer errors. You autocomplete by, after having typed parts of a command pressing tab. If no suggestion comes up immediately, press tab again.

Flags / Options

Basically every CLI (command line interface) program has so-called options, also known as flags. These usually come before the arguments or operands. So essentially:

command [options] [arguments]. All options come in the form of either -option (short) or in --option (full name).

This is an example of the usage of flags with the command ls. The -la option means create a list of all options. The -l and -a options can be specified separately or grouped as in the example below. Usually, when one has more short arguments, they are chained to have a shorter command. The --color option can be used to colour the output. This is the exact command that is executed when you type ll if you used the install script

ls -la --color / Changing Directories (cd)

In Linux, the folder structure is very different from Windows. There are no drive letters. All drives are mounted (you can understand this as being attached) to different folders all originating from the root folder which resides at the location /.

All devices connected to the system are files and these files reside in the /dev folder

Inside that root folder, there are numerous other folders, most of which you do not need to know about. Below there’s a list of the most important folders and what their purpose is.

/bin: Points to/usr/binand contains all binaries (executable files, i.e. all programs)/boot: This folder contains all the files that are needed to start the system and is the mounted boot partition./dev: Short for devices, contains the files for all the devices connected to the system/etc: Contains all system-wide configuration files/mnt: Short for mount. The folder in which there should be folders for mountpoints of additional drives/home: The folder that contains the user folders of all users/root: The home folder of the root user (the most powerful user)/tmp: The temporary folder, a folder in which you can put stuff that you only need once. It will be cleared after a restart.

In Linux, there are also extension-less files. The OS doesn’t only use file-extensions as hints to what this file is, but also the first few bytes of the file itself, which contains information about the file and the permissions. Therefore, extension-less files are possible and might be executable or just normal text files

If you want to navigate your filesystem, you need to move between folders. You can do this by using the cd command, which stands for change directory.

There are a few notable aliases here:

- User’s home directory:

~ - Root folder:

/

If you want to know in which folder you currently are, there’s the pwd command, which stands for print working directory.

You can navigate to your home folder (~) with the following command

cd ~You can navigate to the root folder (/) with the following command

cd /Listing contents of directories (ls)

To list folders inside a directory, there’s the ls command. If you used the install-script, there will also be ll, which will list all files in the folder, also hidden ones. Additionally, the files will be coloured, meaning that you can easily differentiate between folders (blue), normal files (white), executable files (lime) and small arrows are indicating that this is a symbolic link, meaning that this file points to a different folder.

Copying, Moving, Renaming (cp, mv)

These commands are very powerful and have lots of options.

-r: Recursively copy files and directories. If you want to also copy directories, you need to have this option set, otherwise only files will be copied.-v: Verbose. Show what is being copied to where

The -r option only has to be specified on the cp command, as the mv command also includes directories. The destination’s parent folder has to exist!

You can use the mv or rename command to rename directory (=folder) or files.

Assume you want to copy the folder ~/arch-dev-vm folder with the cp command to ~/projects/arch-dev-vm.

cp -rv ~/arch-dev-vm ~/projects/arch-dev-vmAssume you want to move the folder ~/arch-dev-vm folder with the mv command to ~/projects/arch-dev-vm.

mv -v ~/arch-dev-vm ~/projects/arch-dev-vmAssume you want to rename the folder ~/arch-dev-vn folder with the mv command to ~/arch-dev-vm.

mv -v ~/arch-dev-vn ~/arch-dev-vmPython

Python comes directly with your system, as many packages rely on it. You can run any python program with python3 [filename]

pip

Python has a package manager called pip. It can be used to install additional python libraries. On Arch, for quite some time now, pip has been disabled as it liked to break system packages and you are now required to use virtual environments.

You can create a new virtual environment with the following commands. Make sure you are in the directory you want to create the venv (short for virtual environment) in.

python -m venv [venv name here]If the command returns no output, you have successfully created a virtual environment. Now you need to enable it in this terminal to be able to use it. Just remember, it will be turned off, once you close that terminal. You can also use VSCodium’s built in terminal.

source "[path to folder you created venv in]/[ venv name here ]/bin/activate.fish"Omit the .fish if you are using another shell than fish.

These commands create and activate a python virtual environment called main in ~.

python -m venv main

source ~/main/bin/activate.fishPackage management

You can read more about package management here (previous part of the series).

Closing thoughts

This post just barely scratched the surface of what is possible to achieve in a terminal. There might be another post about more complex commands in the future.